Remains of a Tumblr

“This Old Book” was a Tumblr that I started and abandoned around 2012. Most of these posts are also visible over on the blog page, but if I ever start this up again maybe I’ll keep it as a separate series of posts.

“This Old Book” was a Tumblr that I started and abandoned around 2012. Most of these posts are also visible over on the blog page, but if I ever start this up again maybe I’ll keep it as a separate series of posts.

I don’t remember where I found this battered 1972 paperback, some dusty used bookshop of my youth in upstate New York, a bit of a miracle that. Alan Watts is a bit of a complicated figure, an important popularizer of Zen Buddhism in the west. His audio (and video) lectures are entertaining. He had personal failings — alcoholism, marital infidelities — that would seem to contradict much of what he advocated, and it is possible that he did not always paint an accurate picture of Buddhist teachings. But I am fond of him because he got me thinking about Buddhism at an early age, and pulled me back into it off and on over the years, a journey that is by no means complete, one that is in fact barely started. It started with this book, which promises to reveal secrets that adult, polite society did not talk about. I encountered it as my teenage self was finding the explanations of the church into which I was born unsatisfactory. I underlined many passages, starting with this one.

This feeling of being lonely and very temporary visitors in the universe is in flat contradiction to everything known about man (an all other living organisms) in the sciences. We do not “come into” this world, we come out of it, as leaves from a tree. As the ocean “waves,” the universe “peoples.” Every individual is an expression of the whole realm of nature, a unique action of the total universe. This fact is rarely, if ever, experienced by most individuals. Even those who know it to be true in theory do not sense or feel it, but continue to be aware of themselves as isolated “egos” inside bags of skin.

[Originally posted on my discontinued This Old Book Tumblr.]

A recent viewing of the excellent BBC series “Sherlock” sent me hunting my shelves for this softcover pocketbook. This one of the earliest books I owned, perhaps inherited from my father, so it could date to the middle of the 20th Century. It is undated on the copyright page and was published by Award Books Inc. (“Best Seller Classic Series - Specially selected immortal literature, handsomely designed with luxurious, leatherette finish covers. A distinguished addition to all home libraries.”)

Unlike most editions bearing this title, it contains just seven stories, not 12: “The Red-Headed League,” “The Boxcomber Valley Mystery,” “The Five Orange Pips,” “The Adventure of the Engineer’s Thumb,” “The Adventure of the Noble Bachelor,” “The Adventure of the Beryl Coronet,” and “The Adventure of the Copper Beeches.” For a boy of 10 in 1970s America, this England was an exotic and nearly indecipherable place. I eventually sought out the rest (many of them better than the ones in this anthology) as well as many pastiches and inspired knockoffs {“The 7 Percent Solution” was an early favorite, with Sigmund Freud treating Holmes). The BBC series transforms Watson into a blogger, a masterstroke. You could well imagine him typing this opener to “Five Orange Pips” into Tumblr…

"When I glance over my notes and records of the Sherlock Holmes cases between the years ‘82 and ‘90, I am faced by so many which present strange and interesting features that it is no easy matter to know which to choose and which to leave. Some, however, have already gained publicity through the papers, and others have not offered a field for those peculiar qualities which my friend possessed in so high a degree, and which it is the object of these papers to illustrate. Some, too have baffled his analytical skill, and would be, as narratives, beginnings without an ending, while others have been but partially cleared up, and have their explanation founded rather upon conjecture and surmise than on that absolute logical proof which was so dear to him. There is, however, one of these last which was so remarkable in its details and so startling in its results that I am tempted to give some account of it…"

[Originally posted on my discontinued This Old Book Tumblr.]

This book was published in 1991. That means the characters, all in their 20s, were born roughly between 1960 and 1970. I’ve heard the term “Gen X” applied to people born as late as 1981, people who would have been 10 years old and of a completely different culture from the underemployed slackers who make their way through this world of Swedish disposable furniture and McJobs. But somehow the label kept getting applied to younger and younger people during the 1990s. Of course, Douglas Coupland (born 1961) didn’t coin the term; he just popularized it. I bought this copy at St. Mark’s Bookshop when I was 28 or 29 and hanging out in the East Village, visiting friends (I lived in Pennsylvania then). The book inspired a lot of bad newspaper Op-Ed columns by twentysomethings and baby boomers, as I recall, plus a terrible plague of other popular entertainments (“Reality Bites”). But it did capture something about being young and broke in the 1980s. I know the so-called millennial generation (people born around the time this book was published, I guess) are finding themselves in a similar situation. Advice: hang in there.

Sample chapter headings: Our Parents Had More. Quit Recycling the Past. Quit Your Job. I Am Not a Target Market. Shopping Is Not Creating. Purchased Experiences Don’t Count. Define Normal. MTV Not Bullets. Adventure Without Risk Is Disneyland.

The format of the book included marginalia definitions of various aspects of life as a 20something in the 80s/90s. The story is overshadowed by a Cold War ear fear of nuclear destruction that seems quaint now. We have so many other things to fear.

Notably missing: The Internet.

Legislated Nostalgia To force a body of people to have memories they do not actually possess: “How can I be part of the 1960s generation when I don’t even remember any of it?”

[Originally posted on my discontinued This Old Book Tumblr.]

Donald Barthelme was considered the father of postmodern fiction. I acquired and read this book in 1975, before he was dead. Before my own father was dead. It is funny and strange, and I recommend the second half in particular, “A Manual for Sons.” Excerpt:

There are twenty-two kinds of fathers, of which only nineteen are important. The drugged father is not important. The lionlike father (rare) is not important. The Holy Father is not important, for our purposes. There is a certain father who is falling through the air, heals where his head should be, head where his heels should be. The falling father has grave meaning for all of us. The wind throws his hair in every direction. His cheeks are flaps almost touching his ears. His garments are shreds, telltales. This father has the power of curing the bites of mad dogs, and the power of choreographing the interest rates. What is he thinking about, on the way down? He is thinking about emotional extravagance. The Romantic Movement, with its exploitation of the sensational, the morbid, the occult, the erotic! The falling father has noticed Romantic tendencies in several of his sons. The sons have taken to wearing slices of raw bacon in their caps, and speaking out against the interest rates. After all he has done for them! Many bicycles!

[Originally posted on my discontinued This Old Book Tumblr.]

Remember Billy Beer? That is just one of the things that made the brief Carter administration so hilarious. In the late 1970s, Roy Blount Jr. seized on the unlikely election of a Georgia peanut farmer and non-nuclear scientist to explain his home state and the South to a puzzled North (the blurry cover copy above is: “America’s most hilarious writer takes on the whole many angled thing of politics, culture and life”) . It is an entertaining read, with plenty of appearances by Billy and assorted Carter relations, and some moments of wisdom:

The trouble with the world today is that nobody has a handle on it. Hardly anybody. And just because I come from a part of the country whose idea of progressive legislation for many years was an occasional law against “flogging while masked” doesn’t mean that I have no license to lay such a generalized charge.

Let me put it this way: Every single case of anything with which I have ever had the least real iota of experience, personally, has turned out to be either a lot more complicated or a lot less complicated than it had been (and would continue to be) made out to be.

I fault the media, even though I am in on it. …

[Originally posted on my discontinued This Old Book Tumblr.]

Frank Herbert is best known for “Dune,” the famed science fiction novel later expanded to a series. Thankfully, I read those books before David Lynch ruined the story with his movie. This 1972 mainstream work of fiction is currently out of print. I long ago lost my copy of “Dune” and its sequels, but I held onto this, perhaps because of my interest in Native American culture (my college minor). It has a rather dark ending — to say more would be a spoiler — that still feels like a sucker punch years later. The book leaves it to the reader to decide whether the supernatural elements are real or just some type of schizophrenic hallucination. The narrative style is also interesting, with shifting points of view. Is it a great book? After skimming its pages again, I’d say probably not, though I recall being quite impressed with it way back when I was more impressionable. That said, there are no passages as grandly memorable as the famous Zenlike “fear is the mind killer” quote from “Dune.”

[Originally posted on my discontinued This Old Book Tumblr.]

Arthur Byron Cover wrote some cracked science fiction novellas in the 1970s, as part of the “Weird Heroes” and Harlan Ellison’s “Dangerous Visions” series. I used to own a copy of Cover’s “The Platypus of Doom and Other Nihilists,” a mass market paperback that is out of print and as of February 2012 sells for $65 to $100. But this one has survived on my shelf since high school: “An East Wind Coming” is somewhat more easy to get and here is the premise, Sherlock Holmes vs. Jack the Ripper:

It was two million years in the future and they were immortal — Holmes, Watson, all the Great Ones. With nothing to master but limitless Time. But that was before the killing began, bfore the world’s greatest sleuth discovered that history’s most heinous criminal was also “alive” and steeping the East End of the Eternal City in the blood of goddesses.

[Originally posted on my discontinued This Old Book Tumblr.]

I lived with a bunch of engineering students my freshman and sophomore years. At some point, everybody got a copy of this and was reading it. It’s an interesting melange of math, music and art. If you like word puzzles, and recursions and illusions, Zen koans and a dose of philosophy, it entertains. My friends all became programmers and physicists, and I went into journalism, a practical art. We all took something different away from this, I suspect — in my case, a lasting interest in koans and Zen Buddhism. My wife picked this up the other day because one of her students is reading it, but after seeing the formulas and technical material, she put it back on the shelf. It can be tough reading, but it rewards you by stretching the brain.

Jessica Mitford, onetime “queen of the Muckrakers,” blew the lid off the overpriced casket and funeral industry in the early 1960s with “The American Way of Death.” For a while, people were requesting funerals in the “Mitford style” and a “Jessica Mitford” casket — the cheapest available. This 1979 collection includes some of her best investigative journalism and commentary on how she did it. (Mitford died in 1996). The book is a great primer on how think about reporting in a way that makes a difference in people’s lives. When I was a reporter, I often turned back to these pages for inspiration. She also popularized a word, “frenemy,” that some might imagine is of more recent vintage, in a 1977 op-ed piece [pdf]. Her interviewing advice:

Kind questions are designed to lull your quarry into a conversational mood: “How did you first get interested in funeral directing as a career?” Could you suggest any reading material that might help me to understand more about the problems of Corrections?” and so on. By the time you get to the Cruel questions — “What is the wholesale cost of your casket retailing for three thousand dollars?” How do you justify censoring a prisoner’s correspondence with his lawyer in violation of the California law?” — your interlocutor will find it hard to duck and may blurt out a quotable nugget.

[Originally posted on my discontinued This Old Book Tumblr.]

This is a 1979 collection of chapbooks, or literary pamphlets, that were published by Capra. I probably bought it for the Colin Wilson essay about Tolkien, which confessed an admiration for “The Lord of the Rings” when its reputation was a bit more culty and juvenile than it is these days (perhaps). But I am more likely these days to read Henry Miller’s sour, wise and obscenity-laced “On Turning Eighty.” Note the echo of Stevenson in the last line.

Despite the knowledge of the world which comes from wide experience, despite the acquisition of a viable everyday philosophy, one can’t help but realize that the fools have become more foolish and the bores more boring. One by one death claims your friends or the great ones you revered. The older you grow the faster they die off. You observe your children, or your children’s children, making the same absurd mistakes, heart-rending mistakes often, which you made at their age. And there is nothing you can say or do to prevent it. It’s by observing the young, indeed, that you eventually understand the sort of idiot you yourself were once upon a time — and perhaps still are.

[Originally posted on my discontinued This Old Book Tumblr.]

This exquisitely researched book by the novelist Evan S. Connell punctures many enduring myths about General Custer, the Little Bighorn, Crazy Horse and the other Indians who fought there. Buried in its pages are bits of Western lore and historical detail. It is an amazing piece of reportage.

Indians knew it as the valley of greasy grass.

Greasy Grass is the usual translation, although there has been some quarreling about whether it ought not to be Rich Grass or perhaps Lodge Grass, these two expressions being very similar in the Crow language. However the name should be translated, Indians liked this valley and often camped there. Cottonwood trees beside the river provided not only firewood but a sort of ice cream —a frothy gelatin which accumulated when the bark was stripped off and the exposed trunk scraped.

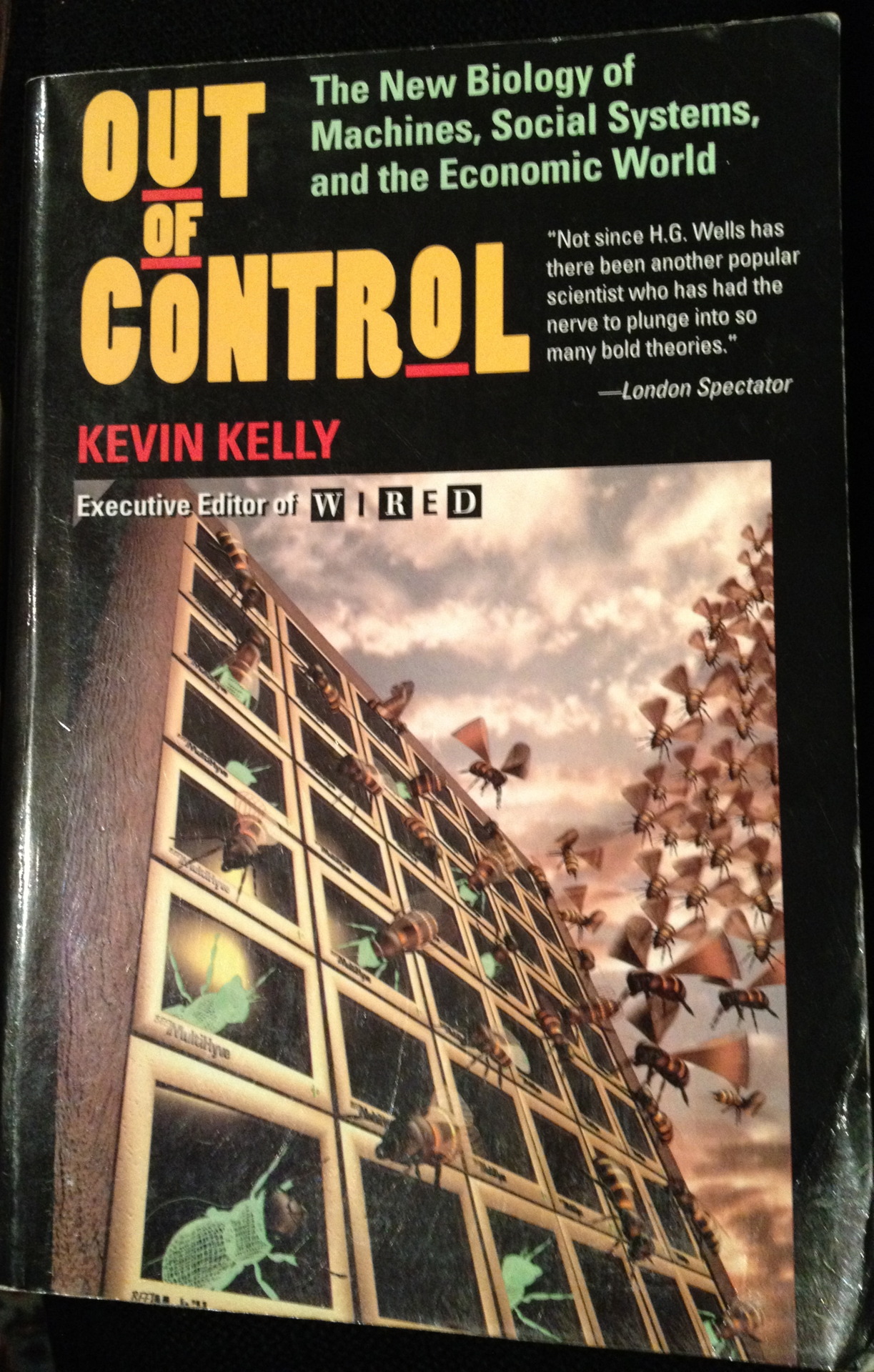

This prescient book, published in 1994 on the eve of the Web age, shaped a lot of my early thinking about technology and media (as did Stewart Brand’s book about the M.I.T. Media Lab). Kevin Kelly was the editor of Wired and previously the Whole Earth Review. The book touched on topics that were strange then, but now more familiar: the wisdom of crowds, the hive mind, gamification, distributed computing and what Kelly called “the marriage of the born and the made.”

For the world of our own making has become so complicated that we must turn to the world of the born to understand how to manage it. That is, the more mechanical we make our fabricated environment, the more biological it will eventually have to be if it is to work at all. Our future is technological; but it will not be a world of gray steel. Rather our technological future is headed toward a neo-biological civilization.

[Originally posted on my discontinued This Old Book Tumblr.]

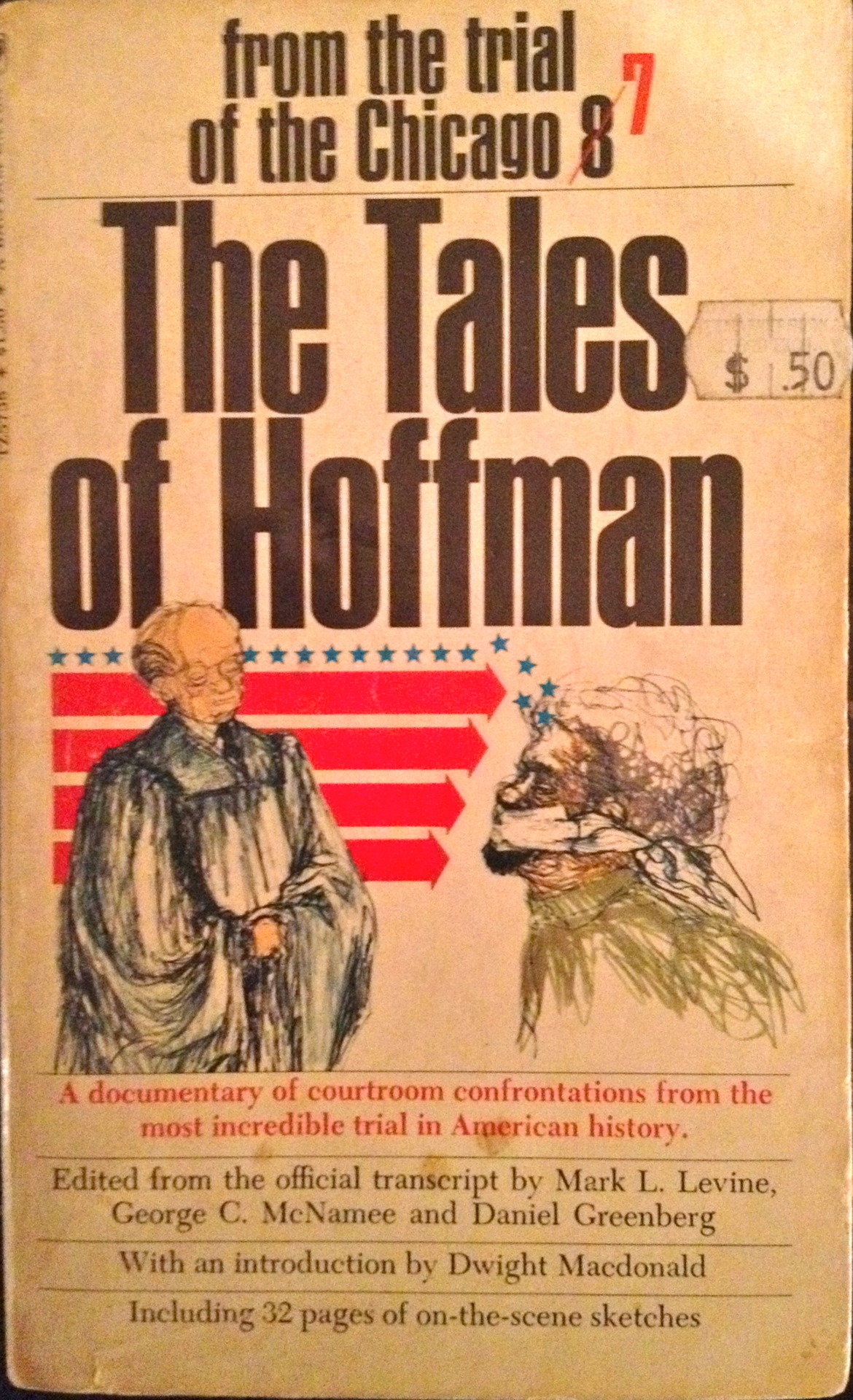

The 1969 trial of the Chicago 8 (later 7) pitted a motley assortment of hippies, yippies (notably Abbie Hoffman) and other leftists against a stern federal judge, Julius J. Hoffman. There was a parade of celebrity witnesses (Norman Mailer, Country Joe McDonald, the Rev. Jesse Jackson, Mayor Richard J. Daley).The resulting courtroom theater played out as farce — with one defendant, Bobby Seale, gagged and bound in the courtroom. A courtroom sketch of the restrained Seale on the evening TV news is one of my vivid childhood memories. This compilation of transcripts and courtroom sketches was released in paperback in 1970.

The Court: Let the record show that Mr. Hoffman stood up, lifted his shirt up and bared his body in the presence of the jury —

Mr. Kuntsler: Your Honor, that is Mr. Hoffman’s way.

The Court: —- dancing around. (Laughter in the courtroom).

Mr. Kuntsler: Your Honor, that is Mr. Hoffman’s way.

The Court: It is a bad way in a courtroom.

Mr. Kuntsler: I remember President Johnson bared his body to the nation.

The Court: Well, that may be.

Mr. Kuntsler: Over national television.

The Court: Maybe that is why he isn’t President any more.

[Originally posted on my discontinued This Old Book Tumblr.]

The cover of this 1992 book looks cooler in the picture than it does in my hand. Through some trick of the light, the pattern looks raised, but it is not. This book contains answers from dozens of famous and not-so-famous people to 50 unusual questions — about their first memories, unexpected moments, treasured possessions, people who influenced them, things worth waiting for, and so on.

It Takes My Breath Away

Norman Lear:

Biting into a ripe peach.

Zar Rochelle:

A Frank Lloyd Wright house. Just the perfection of it. The incredible balance and design and flow.

Gerry Cooney:

Life takes my breath away. There’s a great book out about going through life with blinders on. That was me all my life. I remember one day getting into a glass hotel elevator. I looked downstairs where they had a goldfish pond. And I thought about it. Those goldfish would stay there forever. They’re never going to go anyplace. They’re going to live in that goldfish pond. And that’s how life was for me for many years. To me life is about letting go and being there — really getting out, stepping out. That’s exciting.

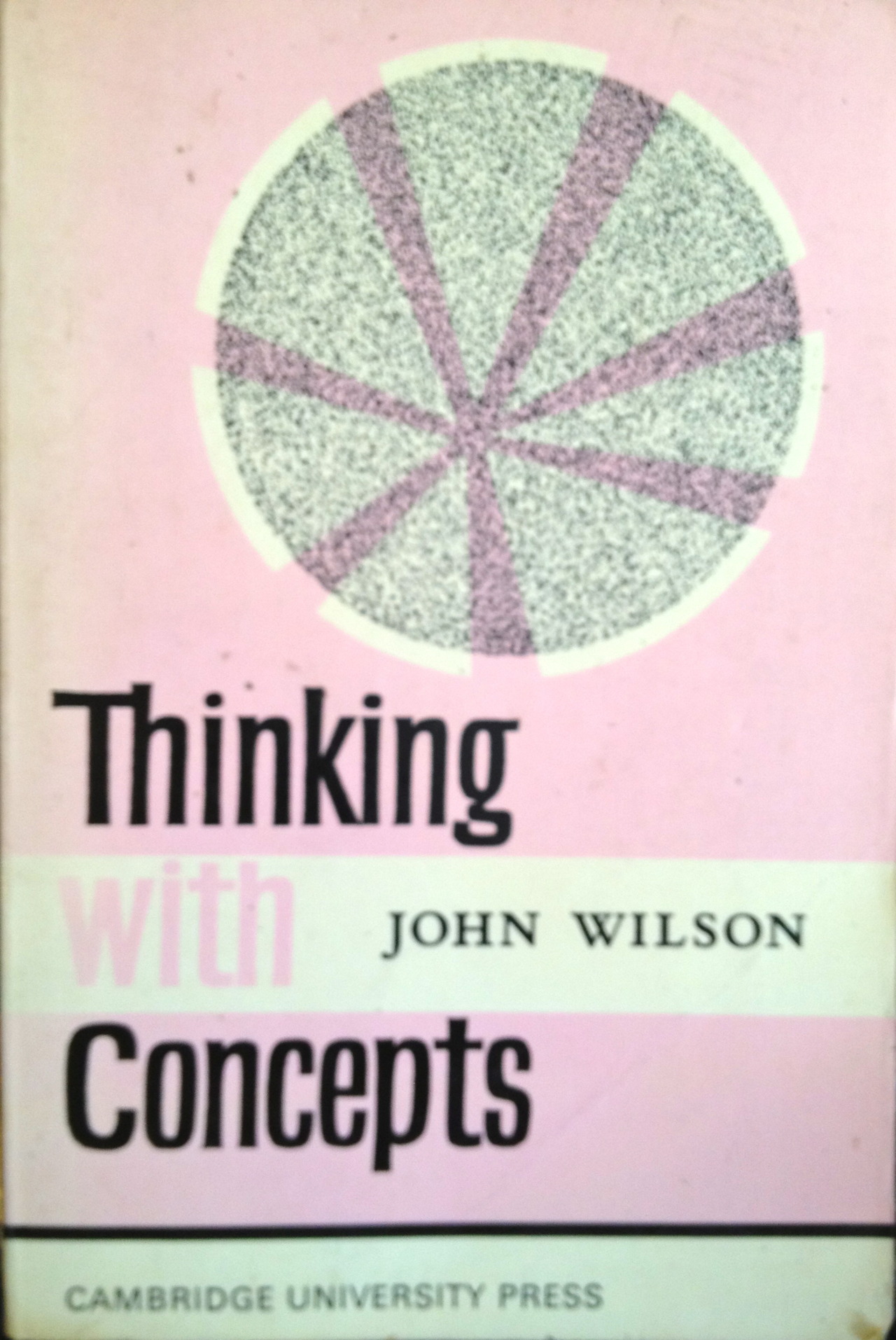

I can’t imagine what moved me to pick up a copy of this book in college. It was not required for any course. But I’m glad I did. First published in 1963, it resembles at first glance a textbook for making good, reasoned arguments about concepts and abstractions. But his prescription for critical analysis (along with examples and exercises) actually improves and clarifies the ability to think, write and argue. It is one of those rare books that made me feel smarter after I finished it. I lost my original copy and tracked down this one on Amazon a few years ago. It was as good as I remembered it, clear and precise, charming and quirky, and very British. This snippet won’t do it justice:

Behind the notion of ‘how to analyze concepts’ , therefore, there lies the still more general skill, ‘how to talk’ or ‘how to communicate’: and to employ this skill we have to learn above all to recognize and enter into the particular game which is being played. Thus the person who yields to the desire to moralise, who cannot talk about concepts but only preach with the, is essentially not playing the game: it is a form of cheating. Similarly, the person who insists on analysing every single concept referred to in a statement is, so to speak, overplaying the game: like a soccer player who insists on dribbling skillfully in front of the goal when he should be taking a shot at it. To communicate, then, involves recognizing the particular game and playing it wholeheartedly.

The newspaper columnist Mike Royko wrote this detailed portrait of Mayor Richard J. Daley, the head of the 1960s Democratic machine in Chicago, in 1971. I can’t remember when or where I first acquired it, but at some point I lost my copy. Then my wife found another one buried on a bookshelf at her mother’s house. I’m glad she did. The book is part indictment, part admiring profile, of the mayor and the corrupt city that raised him and how it all spun out of control with the police brutality against protesters at the 1968 Democratic Convention. Here’s a description of the notoriously corrupt Police Department of the Daley era:

Not everybody was on the take. There were honest policemen. You could find them working in the crime laboratory, the radio lab, in desk jobs in headquarters. There were college-educated policemen, and you could find them working with juveniles. There were even rebelliously honest policemen, who might blow the whistle on the dishonest ones. You could find them walking a patrol along the edge of a cemetery. The honest policemen were distinguished by their rank, which was seldom above patrolman. They were problems, square pegs in round holes. Nobody wanted to work in a traffic car with an honest partner. He was useless on a vice detail because he might start arresting gamblers or hookers. So the honest ones were isolated and did the nonprofitable jobs. It had to be so, because a few good apples in the barrel could ruin the thousands of rotten ones.

[Originally posted on my discontinued This Old Book Tumblr.]

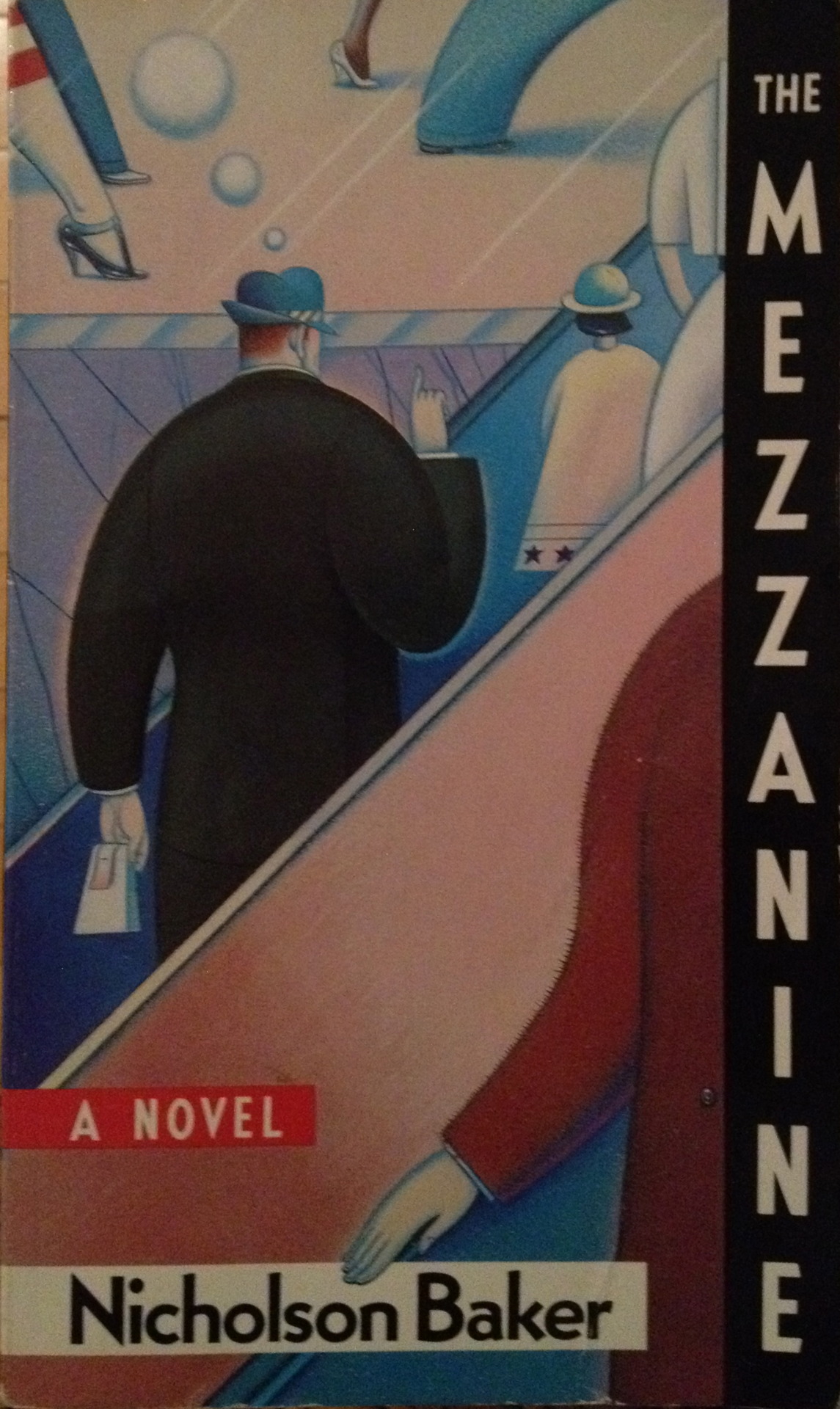

All 15 chapters of this 135-page novel with footnotes take place in the mind of the protagonist as he ascends an escalator in his office building’s lobby. There is quite a lot about shoe-tying and laces, also. Nicholson Baker became much more famous, and his books much stranger, after this first effort in 1986.

[Originally posted on my discontinued This Old Book Tumblr.]

When we were teenagers, a friend of mine and I used to crack up reading this when it first came out in 1976. We also loved Woody Allen's movie “Sleeper.” Some of this material has aged better than Allen or his reputation.

Here's the opening paragraph to “Selections From the Allen Notebooks”:

Getting through the night is becoming harder and harder. Last evening, I had the uneasy feeling that some men were trying to break into my room to shampoo me. But why? I kept imagining I saw shadowy forms, and at 3 a.m. the underwear I had draped over a chair resembled the Kaiser on roller skates. When I finally did fall asleep, I had that same hideous nightmare in which a woodchuck is trying to claim my prize at a raffle. Despair.

A 1991 collection of games and other provocations developed by the Surrealists. An example: “Would You Open the Door?” One member of the group names a person, famous, infamous or known to the group. The rest write down whether they would let the person in, and explain why or why not.

No, consigned to the textbooks. [J-LB] Yes, through wanting to get it over with. [RB] No, nothing to say to each other. [AB] No, too caught up in his theories. [EB] No, seen too much of him! [AD] No, so dreary! [GG} Yes, suppose so, but conversation might wear a bit thin. [JG] No, boring. [GL] No, urge to laugh. [SH] No, I’m afraid his intentions prejudice his painting. [WP] No, too stupid. [BP] No, I have my window. [JP] No, no time to waste. [BR] No, hate apples. [JS] No, since I love apples. [AS] No, enough of still lifes. [T] No, I like fruit too much. [MZ]

[Originally posted on my discontinued This Old Book Tumblr.]